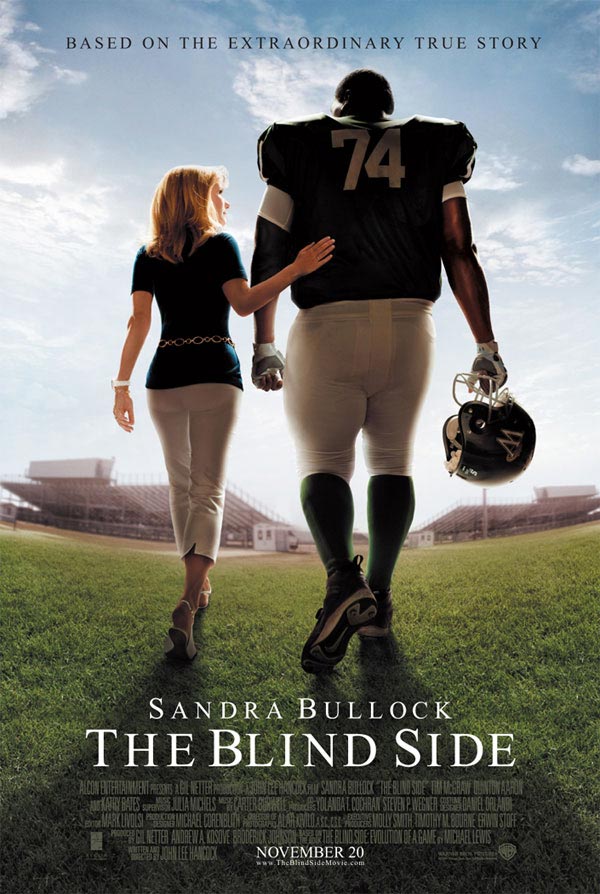

I’ve been vaguely aware of both the plot of The Blind Side (homeless black teenager from broken family is adopted by wealthy white family and goes on to play pro football) and the critiques of its racial politics for some time, and despite its unexpected box office success, I’ve had little desire to see it. I’m currently in Florida visiting my grandmother, though, and she wanted to see The Blind Side, so see The Blind Side we did.

I’ve been vaguely aware of both the plot of The Blind Side (homeless black teenager from broken family is adopted by wealthy white family and goes on to play pro football) and the critiques of its racial politics for some time, and despite its unexpected box office success, I’ve had little desire to see it. I’m currently in Florida visiting my grandmother, though, and she wanted to see The Blind Side, so see The Blind Side we did.

I don’t much care for Sandra Bullock, but she’s exactly as good as everyone says she is as the loving, no-nonsense matriarch of a wealthy Southern family. And the movie in general is pretty much what you’d expect: cutesy, saccharine, uplifting, and formulaic. It’s good for what it is though, with a remarkable story, quick pace, witty dialogue, and genuinely likable characters.

As for the film’s racial politics, I can’t say that I entirely agree with most of the critiques I’ve seen, though I do have a few of my own. A. O. Scott’s review for the New York Times encapsulates the most common criticism of Blind Side:

To the extent that Michael represents a social problem (or maybe a whole bunch of them, including poverty, drug addiction and family dysfunction), the solution depicted is individual, charitable and, at least implicitly, faith based.

The fundamental problem with this critiques is that it expects entirely too much from a movie and from an individual. Granted there is a temptation to read more into it, but The Blind Side is a small movie about one person and one family. It is not a polemic, and it is not an overtly political documentary. It does not explicitly advocate anything. It simply tells the story of one extraordinary woman who welcomed a complete stranger into her home and loved and cared him as her own son.

I don’t think the film has to be interpreted as a statement about either the causes or or the solutions to social problems like poverty and drug-addiction, though I would certainly disagree with anyone who maintains that private charity is a sufficient solution. Granted, The Blind Side is all but silent regarding the circumstances of Michael’s youth and the complex web of forces, both social and individual, that dooms so many young men to the violent death that Bullock’s character, Leigh Anne Tuohy, realizes, via internal monologue voiceover, could easily have been the fate of her adopted son. But I don’t think that every artist who touches on a theme like poverty is obligated to explore every facet of the problem and offer a solution, and in fact I think all but the best art does well to steer clear of such overt politicism.

I also don’t think that Tuohy’s behavior is charity, precisely. Charity is fundamentally an economic relationship, not an emotional one. The vast majority of charitable dollars given in the US are donated in a disconnected way. People give money either directly to a panhandler they barely know and will probably never see again, or indirectly through a large organization that pools and distributes their money, again almost always to people they do not know and will never meet. Motivations for charity are varied and complex. They usually include good will, but they rarely include love, at least not the kind of emotional, interpersonal love that a mother has for a son.

This is the real limitation of charity, the reason why the critics rightfully consider it an insufficient solution. People will give enough to alleviate immediate suffering, but rarely enough to prevent future suffering or change underlying conditions. It is all well and good for the relatively wealthy to give their excess, to give what they have above and beyond what they feel they need, but few are willing to sacrifice for strangers in the ways that they would for their own children.

This is the remarkable thing that Leigh Anne Tuohy did, and while it is not a large-scale solution, it is as much as many individuals can accomplish and more than most, critics of The Blind Side included, will ever do. Private action is absolutely not a substitute for government action and institutional change, but too many people use their inability to accomplish the latter as an excuse not to attempt the former.

My own problem with the Blind Side is that it makes everything look so easy. This is both an artistic problem and a political one. As a film, Blind Side lacked conflict. I’m struggling to remember a single problem that occurred that wasn’t resolved within minutes of its introduction, and I couldn’t tell you what the central conflict of the film was supposed to be.

This is a political problem because Michael is too easy. He is a perfect son, easy to get along with and unfailingly polite and lovable from the moment the Tuohy’s take him in. Michael is easy to love, and this is what makes The Blind Side‘s message about the power of love so fundamentally weak. There are plenty of endangered children who have as much potential as Michael, who are as deserving of love and opportunity as Michael, but who are not such easy children. They fight, they steal, they use drugs, they join gangs. They need loving, caring adults in their lives at least as much as a “gentle giant” like Michael does, but they have far more trouble finding the support that they need.

It’s certainly unfair to compare a mainstream Hollywood production to a great American novel, but I’m reminded of Richard Wright’s introduction to his novel Native Son. Wright, who had previously written Black Boy, an autobiography about his own childhood experiences with poverty, racism, and hunger, chose a far more controversial protagonist for Native Son. The fictional Bigger Thomas is a thug, a thief, a murderer, and a rapist. Wright does not ask us to love him, but he does ask us to understand him and to see him as both a villain and a victim.

Wright realized, after Black Boy, that he needed to give his audience a challenge. Wright himself was too easy a young man to sympathize with. Bigger Thomas forces us to sympathize with a far less sympathetic character, and in so doing, makes a far stronger statement about the effects of racism and poverty.

The best indication that The Blind Side doesn’t advocate private charity as the be-all and end-call to social problems is that this solution is most explicitly proposed by Leigh Anne’s predictably patronizing and snobby country club friends, who seem willing enough to donate and host fundraisers if Leigh Anne is organizing a “Project for the Projects.” What these ladies lack is genuine concern of the sort that would compel them to pursue meaningful change or follow through on such an initiative. While it would have been nice to see Leigh Anne radicalized by her relationship with Michael, ready to invest her considerable resources in a larger-scale solution, her life and story are still an inspiring example of the love that is necessary to accomplish real social change.

What Leigh Anne will not accept for Michael, no parent, white or black, should accept for any child, white or black: no roof over his head, deteriorating clothes, ignorant teachers, and threats from drug dealers. Yet these are exactly the outcomes that millions of American parents, white and black, would never tolerate for their own children but are willing enough to accept for other people’s children. Real improvements for children with troubled lives is going to require the relatively privileged to extend their circle of moral concern to include more than their immediate families, to care enough about all children, even and especially the most difficult cases, to protect and fight for them the way Leigh Anne does for Michael.

Excellent write-up! I have not seen the movie yet, and after reading a couple early reviews, I had bought into the criticisms of it as racially offensive. Then a few of my friends saw and reported on it and dismissed those criticisms. As you indicated, it also considerably outperformed expectations at the box office. I want to see it, too.

Interesting re: the distinction between charity and love is that the word “charity” originally was used to refer to the highest possible form of love rather than an act of caring devoid of real emotional attachment. The OED is not freely accessible online, but here is the wikipedia entry for charity: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charity_(virtue)

Nice catch, Calmer…in relation to: “Charity is fundamentally an economic relationship, not an emotional one”…I was just about to say you’d wanna check with Aquinas on that one.

Saw the film. My soul shrinks by 1% ever time I see a Sandra Bullock film.

Interesting. I actually managed to get a philosophy degree from the University of Chicago without ever reading Aquinas. Still, I stand by my assertion that most modern-day charity is primarily driven by some combination of pity, guilt, social pressure, and self-aggrandizement. There’s rarely an interpersonal element to it, certainly nothing approaching the level of affection and concern that generally passes between family members.

One of Kurt Vonnegut’s lesser known works explores a near-future where everyone in the US is assigned a color, or maybe it was a number. In any event, whenever you met someone who shared your color/number, you were supposed to help him unconditionally and in any way that you could. The idea was to guarantee that everyone had a family to help and support him.

Vonnegut’s more popular God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater explores a similar theme. Eliot Rosewater inherits the presidency of a large family foundation and ultimately gives himself up completely to the people the Foundation seeks to help. He grants all requests for assistance and answers phone calls personally at all hours of the night. While it could be argued that he is actually taking the Foundation’s stated purpose as seriously as possible, his heirs point to this behavior as proof of his insanity and attempt to have him removed from the office so that they can control the fortune.