I just published an article on a friend’s blog entitled “Your Information Diet“.

What much of the discussion about “bubbles” ignores is that it matters a great deal what kind of opposing information you consume. Even worse than an echo chamber – and, frankly, a better description of the contemporary mediascape – is an environment in which individuals are exposed to a combination of passionate advocates for beliefs they already hold as well as unsavory representatives of opposing viewpoints.

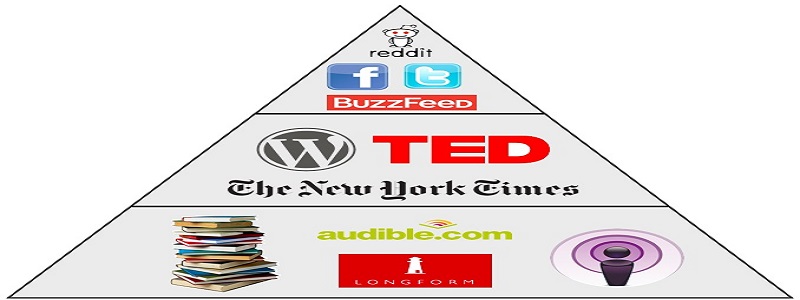

This is why it is so important to take responsibility for your own information diet. Genuinely challenging yourself is important, and you cannot rely on a partisan to provide you with a reliable representation of opposing points of view.

I’ve been increasingly troubled by people who cherry-pick particularly poor advocates of a given policy or formulation of a particular argument and then point to their badness as “proof” that the policy or argument is fundamentally flawed. I’m convinced this is essentially a variation of the Straw Man Fallacy, and while I’m sure that many people do this unintentionally, I also think that more sophisticated ideological media outlets do it more deliberately.

This causes problems in a lot of ways, not only by skewing the thinking of individuals but by amplifying the voices of folks who are essentially professional trolls. The most rabid pundits end up getting promoted by ideologically sympathetic media and hate-promoted by ideologically opposed media. It’s win-win for them, and the quality of our public discourse is the loser.

I wrote this piece about how, as citizens, we need to take responsibility for seeking out and challenging ourselves with the strongest adherents of ideologies opposite to our own, rather than looking for punching bags. It probably reads like a lecture, but rest assured: I am myself a big part of the target audience.

I like the article and the explanation of inflammatory mechanisms seems quite important. I think though the discussion still adheres too much to the way people are discussing American media/democracy, its false dichotomies and laughable premises. Not that you the author has been anchored or misled by that, but that’s where the discussion is, unfortunately, so that’s where you’ve got to try to stake some ground.

Another tactic the media utilises well often enough is to be right on one (or most) thing(s) so they can be wrong on another. Russian media sees value in getting stories right where they aren’t directly interested because it builds credibility for propaganda they publish when they are. The American media does this a great deal despite not being state run. The New York Times tries to get a lot right, and then publishes fawning articles about the dictators in Saudi Arabia — the credibility they’ve built up elsewhere helps them push through the abandonment of values they try to shout through a megaphone elsewhere (along with the target audience not being subjects of that dictator but rather potential supports and business partners).

I think some naive or ‘conspiratorial’ observers of this look to the ownership models and then, since often who owns media is not that well advertised, believe there is actually a mechanism between the state and the media owner that trickles down into Thomas Friedman columns (to stick with the Saudi Arabia example). Actually I think Friedman is an idiot on his own. The sort of searching for who owns a giant enterprise like the New York Times over-ascribes power to those at the top of a huge machine, underestimates how difficult (impossible) it would be for a place like Washington to communicate marching orders to a broadsheet, while under appreciating the ideological soak Americans experience to get to a place where they can get free trips to Riyadh for the New York Times. Too many political and media observers seem to point out a concentration in ownership somewhere and then point back to their point and go “Seeee???” as if their point had been made. Any concentration in ownership is an opportunity for someone to prove something without mechanism — guilt by concentration, like by association.

Getting back to your piece, I think that these sort of epistemological trainings are not going to go far while other facets of political philosophy remain absent. For example, many people in the West join or support a political party. This is what I call a ‘first move’ mistake. You can’t recover after playing H3. You will be forever biased to apology (and/or worse, viewed as such) for those whose ranks you’ve joined. Moreover such a move is unnecessary. At no point in your citizenship will you not be allowed to vote, run for office, contribute to public debate, or ask questions at a town hall having not joined ranks with a party. Oh but I [italics] am the exception! You say. I [italics] can join Party X and work for Candidate Y and still be a critic of X and Y. Congratulations, you [italics] are one in a million, the point is not unmade. Not that I believe you.

Anyways (I know the forthcoming is restatement for just about everyone reading this, please bear with me) this seems most poisonous in the American context because there are two nearly identical parties operating in some kind of cooperative competition. Those who accept this still somehow find themselves defending the drone king by/while attacking the donald. This gets to the next point missing on my political philosophy checklist: abhorrence of statism. I don’t know what the definition on statism is these days, but I mean it as ‘endorsement of the idea of Westphalian states as legitimate actors, taken for granted, the product of a progress of human political organisation.’ This would be in contrast to seeing Westphalian states as the dominant political organisation de jour, on no other firm presupposition other than that they prevailed and are here now.

We should be critical of states and critical of power. I suppose I have been terribly naive in assuming most active critics of the west get this, but it turns out, some actually think certain states more virtuous than others (in what part of these virtuous states’ nature I’d like to know, since if you burrow down to the essence of any state at some point you’ll find there is nothing, just an otherwise vacuous room of flag designs and dubious, poorly told anecdotes). Again, one need not endorse an alternative — I think that mistake gets made too. Simply because I don’t take states for granted does not mean I cannot make criticism that suggests reform over revolution. Simply because I don’t see them as truly legitimate does not mean I need to, in order to critisize the deploy of their powers, imagine an entire universe of alternative political organisation. Don’t be ridiculous. Yet so many defenders of statism (I mean those who would defend in theory, not specifically, the US exploding children in Raqqa and Mosul, or Canada’s involvement in the destruction of Afghanistan 2001-present) are ridiculous in precisely that way.

Do you see what I am getting at? It is the perspective that “there is a right, a good candidate out there. But it is not this [italics] guy!” That perspective is highly self-deceiving and without some reading of political philosophy it will persist. And the tragedy is that it is wholly unnecessary for one to function in solidarity with oppressed people, or as a jobsworth taxpayer, or as a diligent Edmund Burke contributor to the public sphere in one’s polity. I think that’s another part of my naivete actually. I just sort of assume halfway through Machiavelli any reader will have this lightbulb moment that all politicians should be viewed as scum of the earth as to optimise any citizen’s perspicacity and agency.

Anyways that is all sort of on the point of American dichotomies. I know your article mentioned that there are often more than two sides to the story. But I still felt it pandered a bit too much to the idea that there are just two. My point being that idea most benefits power. So when we create dialectics (I’ve lost my last reader now I’m sure) that pander to this two-side-ism, we are somehow either catering to power, or being catered by power, whether we like it or not.

What I feel is really lacking from the discussion (and I certainly don’t take you to disagree with this, it would be surprising!) is reading and abeyance. Contentiousness often dissolves upon further inspection. Deep reading equips one to win arguments but the rub is it also dissolves one’s insecure desire to win arguments. The more one reads on something the less convinced one becomes of the need to stake out a position on something where view-formation could be held in abeyance without penalty. Meanwhile, people are unskilled at both listening and at recognising that something is not an argument. Often those same people can be inspired, or cued, to better their own view-exchange behaviour. I see this happen in (small) rooms all the time. If you convince someone else that you are reasonable and are currently being reasonable (maybe even more important than this is convincing them that you are polite!), mutual abeyance will often be organically exercised. “We recognise that we disagree and the sorting out of where and how we do is interesting and sufficient” will often go unsaid in a conversation that could have been an argument. That is not easy on an empty stomach.

This is just an extraordinary bit of writing and something I very much needed to read. There’s not much I disagree with as an academic point, though some of this thinking is so deeply ingrained in our world (well, *my* world – I suppose we occupy quite different worlds these days, which is probably why your perspective is so much better) that it’s hard to account for in my everyday speaking and living. Hence my admittedly insufficient disclaimer at the end. Of late I’ve felt like there are so many little fires right around me to put out that I’ve neglected the bigger ones. But maybe that’s more like rearranging deck furniture on the Titanic. Or perhaps worse, it may be that the “little fires” actively serve the interests of the bigger ones by forming such a distraction. Until eventually one of them burns out of control.

Thanks for writing!

You (or Gareth) familiar with “Manufacturing consent” by Noam Chomsky, cause to me that was such an eye opener, I highly recommend it in case you didn’t read it…